4 Things I Learned From Running a 50k Ultramarathon

Hundreds of training hours, hundreds of training kilometers, and several liters of combined blood, sweat, and electrolytes later, here we are at the end of the 50k fundraiser run. We ended up raising $1872.63 for the REAL Program - almost $900 past the original goal. I’d consider the whole thing to be a huge success. So a big thank you to everyone who donated, spread the word about the fundraiser, or supported to make it that way.

Prior to this little trail running side quest I was involved with powerlifting and pretty head-and-eyeballs into the pursuit of becoming a big burly boy. I remember about 2 years ago standing in the gym giggling with two of my coaching friends at the prospect of me ever running an ultramarathon because it seemed so ridiculous. That same mentality gradually shifted to me being intrigued by the challenge of training for something that seemed so out of reach, and so polar opposite to any training goal I’ve went after before. The tickle became an itch, and eventually I committed to running a 50k trail race - both to see if I could, and see what I could learn along the way. This article is a debrief of what my training plan looked like and the 4 biggest lessons I took away from the whole process. (Just how I structured my own training, not how everyone should do it - I'm no distance running expert). Looking back on it now I can confidently say that this whole endeavour has lead to some ideas that will shape the way I look at training for a long time. These things have already had an impact on the way I look at structuring a training approach, so I hope they’ll do the same for you too. I’ll start with a little description of each of the 3 broad phases of the prep which I’ve broken up into 3 phases that I’ll call “General Preparation”, “Specific Preparation” and “Fully Running Focused”. Phase 1: General Preparation

The main goal of the phase was just getting my body to a place where I could use running as a mode of exercise to push my body.

Before I thought about training for a 50k, I was pretty much just training to get jacked. The only activity I was doing outside of lifting was going for walks and a weekly rock climbing session, which weren’t the greatest ways to prepare to run on trail. On top of that, I have a history of a couple broken ankles and structural issues related to that, as well as a history of on and off knee tendinopathy. At the time of having the idea to train for trail running both these things weren’t an issue, but both had thrown a wrench in productive training in the past, and I knew they had the potential to derail my trail running too if not addressed. I needed to get to a place where my endurance was the limiting factor for my running - not how long my joints, muscles, or tendons could hold up.Weight Training in Phase 1

The meat and potatoes of my strength training sessions across the whole prep were based on movement variations from the following categories: squats, hinges, upper body pushing, upper body pulling, lunges, and torso work. The main way I addressed the problem of my body not being prepared to use running as a training mode yet came through the smaller stuff that I fit around the major movements to fill in the gaps. One of the biggest “gap fillers” were extensive plyometrics - they’re not the type of plyometrics where you’re doing one jump as high as possible, but the kind where you’re doing many tiny jumps for as long as possible. That’s essentially what running is when you break it down, so this was a good way of increasing my tissue’s capacity to handle impacts over the course of a big ol’ run.I also began with some intensive plyometrics (that’s the “one jump as high as possible” kind). These were mostly done emphasizing proper landing technique so I could safely get into higher intensity plyometrics later in the training program and use them to work on force absorption and power production.To build capacity in the other key areas that would overlap with running, I did some exercises to strengthen the muscles surrounding my ankles that don’t usually get trained, like different calf raises, tibialis anterior work, and some foot strengthening. My favorite Tibialis Anterior movement from the training - Kettlebell Tib. Ant. Raise

Total weight-training volume decreased across across 5 gym-sessions this first phase to make room to gradually add in some running. Intensity increased to prepare me to get into more strength ranges later on in the prep. Overall both volume and intensities were still in the medium range, as this was a bit of a transition phase from going full high rep bodybuilder meathead mode to more of a strength focused period of training in the weight room. Run Training for Phase 1

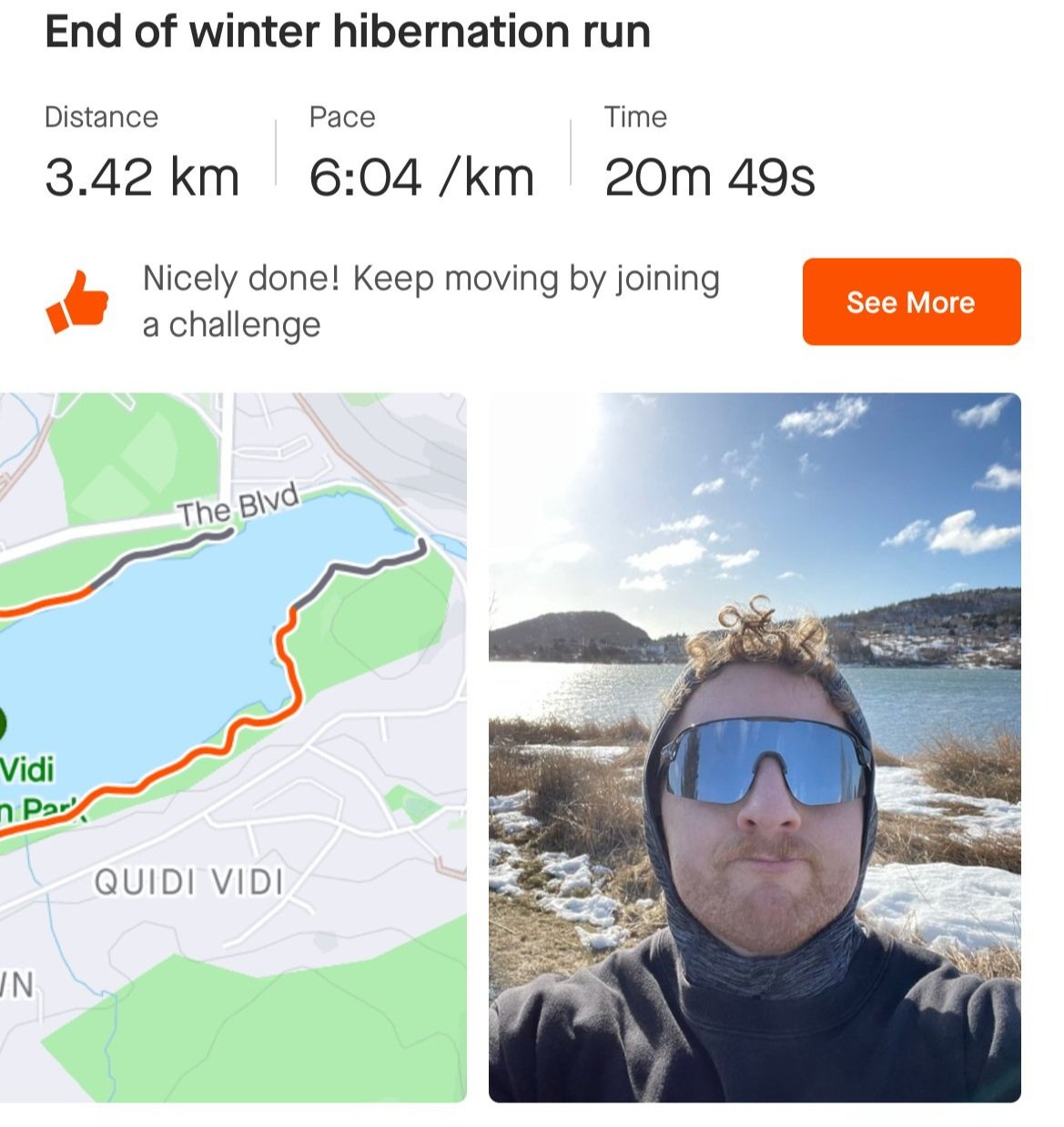

Toward the last couple of weeks of this phase when I’d built up enough tolerance to plyometric loads, ankle strengthening, and other key areas I added in my first run on Saturdays (along with an afternoon arm-pump bro session on the same day, for balance.) This first run was 3.5k, and definitely felt like I had done a run, but without the slightest sign of joint pain. I felt like I could have comfortably maybe done 1-2 more kilometers if I really needed to. Speed glasses also very important.

Phase 2: More Specific Preparation

The main goal here was increasing weekly kilometers while maintaining my base of strength. Things got more running specific - probably 60% priority on running, and 40% on lifting where I could now use running as a way to increase my endurance, and was starting to have to worry less about the rest of my body holding up. Weight Training in Phase 2

During this second phase the weight sessions started to look like proper strength sessions - strength is more intensity driven and the running was more volume based, so I could maintain my strength while pushing the running volume with less interference. My main movements across those 6 movement categories moved more towards variations that let me handle heavy loads and train for strength - trap bar deadlifts, barbell back squats, barbell bench press, weighted pull-ups. Plyometrics in warmups got more intense, but most of my extensive plyometric needs were now being taken care of by increasing my running, so I gradually phased them out to avoid “double-dosing”. I kept some of the ankle strengthening around for a little longer even though it also had overlap with running, but that all got taken out by the end of the phase as well.Weight training volume took a more aggressive dive where I was now working in rep ranges 5 and below and went from 5 gym days to 4. This left room for even more running volume. Intensity gradually progressed upwards, as I got used to handling heavier weights. Even though the running volume was increasing steadily I actually managed to make some strength progress across this period, all while keeping things at pretty moderate relative intensities. Run Training in Phase 2

Gradually over the course of about 8-10 weeks in this phase I upped the run frequency from 1 per week to 3. The general pattern of doing this was to increase the kilometer-age of existing runs for ~2-4 weeks. Then I’d keep the weekly kilometer increase around the same, but add in another run the following week, then repeat the whole process. I found 3 runs was a good place where I was making good progress on weekly kilometers, wasn’t totally wiped all the time, and could fit it all in with my other commitments. An example of the pattern I used to increase running frequency.

Gone was the Saturday arm pump (RIP) and Saturday’s only session became a long trail run. I did my other runs in the later evenings, and my weight room sessions in the earlier mornings. There’s some research out there showing that it’s better to do this the other way if your main goal is aerobic endurance, but my logic behind this was that I would rather run with heavy legs (which I was going to be doing a lot of over the course of 50k) than doing my heavy strength and power work with post-run legs. It was against what the research said, but helped me stay consistent with the training and therefore worked out pretty well. When runs eventually got to 3 per week, they’d look like this:Run 1: ModerateOn road, moderate/comfortable pace, moderate distance 10-22km (depending on how close the 50k date was)

Run 2: SpeedOn road, intervals between uncomfortable fast pace and comfortable pace, short distance between 6-12km (also depending on how close the 50k date was)

Run 3: Long TrailOn trail, slowest pace (due to terrain and walking steepest inclines), longest distance 15-36km (depending on how close the 50k date was)

I didn’t worry too much about exact paces where I was fairly new to running. My comfortable pace for road runs was just dictated by if I generally felt comfortable or not. My uncomfortable pace would be the same sort of thing - if I was breathing heavily and it sucked a little I knew it was fast enough. For the long trail runs I didn’t care about pace at all. It’s common practice for long distance trail runs to walk the big inclines and run everything else, so that’s what I did. All I monitored was elevation and distance, making sure I was progressing gradually towards 50k and around 2500m elevation gain.Phase 3: Fully Running Focused

By this point I was well serious about running 50k, so the main goal was to increase my weekly mileage to a point where I could be confident in my ability to handle 50k all in one shot. With the mileage getting pretty high it meant that the weightroom had to fully take a back seat for a bit to leave room for the running. Movements were almost entirely compound at his point, aimed at maintaining strength and plyometric ability. The only isolation exercises that hung on to this point were things that helped keep my joints and muscles feeling good, like some paused knee extensions to help my knee tendons and some full range of motion calf raises to stretch out my tight calves. Everything that might overlap with running was taken out - no more skipping, stressful ankle work, volume work, etc.. The gym sessions consisted more or less of moving something fast, then moving something heavy, then a couple small things to take care of my body, and then gettin' out of there. Volume was minimal where the running volume was going through the roof. Gym sessions dropped from 4 to 3 and eventually to 2 per week. I tried to do just enough to maintain strength and nothing more. On that same page, intensity wavered between moderate and high. This was also done in an effort to maintain my strength while working around running fatigue. Run Training in Phase 3

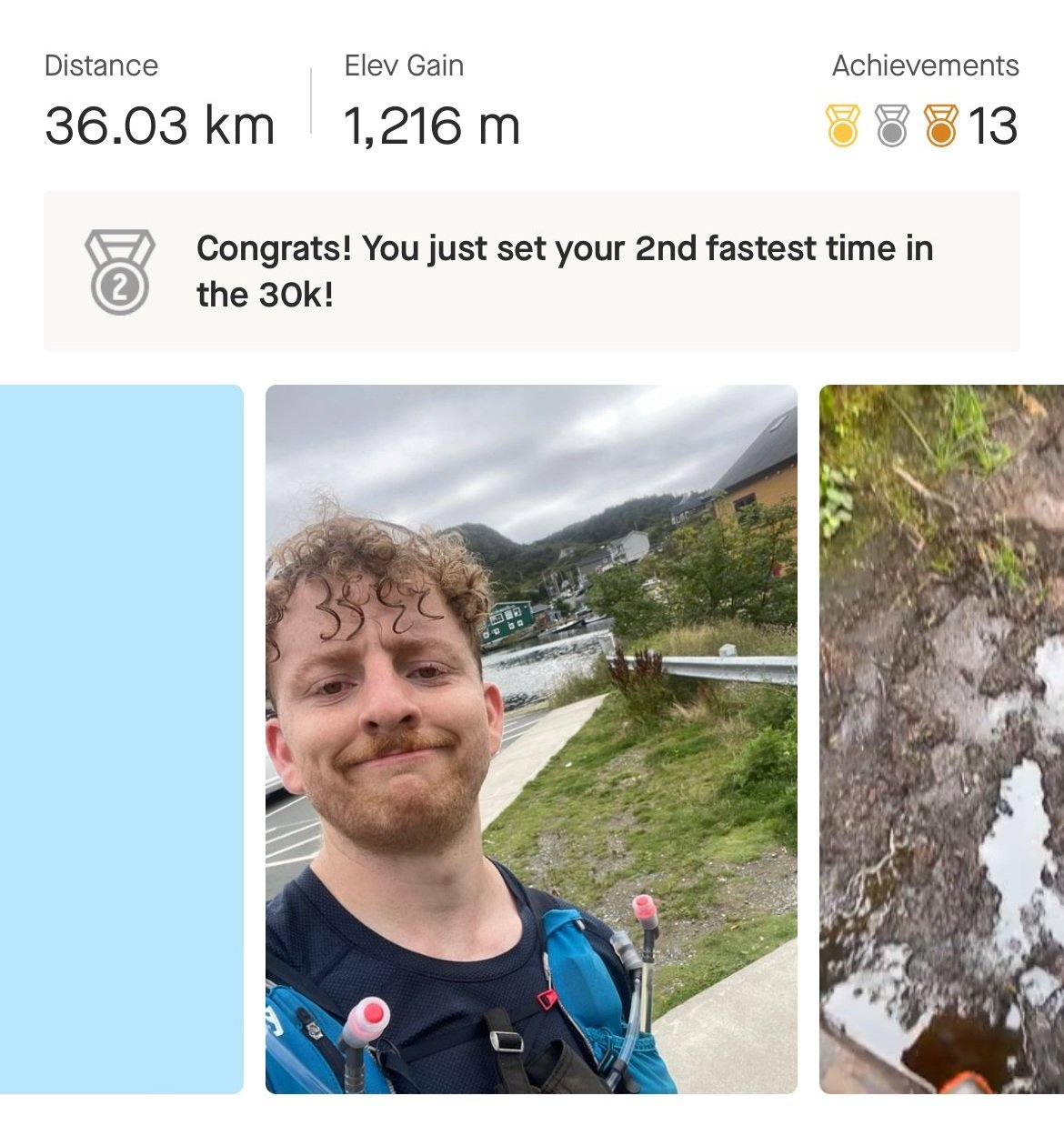

This part was a bit of an experiment of mine with no real evidence to support it that ended up working well. My mileage goals to work towards in my highest week of training were a long run of around 30-35km, and to put together 2 runs within a few days that equaled more than 50km. I figured if I could put together more than 50k between 2 consecutive runs then I’d be able to slog through 50k in one go.My highest week before tapering ended up being:Moderate run: 18kmSpeed run: 11km intervalsLong trail run: 36kmFollowed by next week’s moderate run of 22km a day or two after

My longest training run.

Between the 36k trail and the 22km soon after I had 58km which well surpassed my goal of 50k between 2 runs. The total kilometers of the week prior ended up being 68km. So I had my two markers that if I would ever be ready to try 50km, it’d probably be now after a nice taper.The Taper

I will definitely not claim to be an expert in the perfect running taper, but the basic concept is to give yourself, your joints, your muscles, and your brain a nice long rest before your big event. So I took a week and a half after my last 22k training run where I did minimal activity in the gym or running - just a couple of 3-6k trots, some yoga, and bare bones weight training to keep myself moving while letting all the fatigue dissipate and trying not to get hurt the week before the 50. The main priorities were sleeping and eating, neither of which I had any trouble doing because by this point I was absolutely wiped. The official 50k Strava post. My last Strava post for a while…

Post 50k Thoughts

The 50k ended up actually being a 56k due to some route planning and navigation errors made by me. Thankfully the 50k mark happened in the middle of the woods so I didn’t really have much choice but to keep pushing for the end where I had a ride home and a fresh pizza waiting for me.I totally understand why people say ultra distances are more of a mental challenge than a physical one. When my head was in a good place the running was easy and sometimes even fun. The minute the switch flipped to thinking about how long I had left, or how sore my body was, things got a million times harder. Overall I’m pleased with how physically prepared I was. I had very little joint pain (aside from a small amount you’d expect running 56km at close to 200lbs). The second and third phases of training seemed to have gotten me to a place where my mental state and how much food I could stomach were the limiting factor of wether I kept running or not. I’d be interested to get someone’s opinion who knows more about these ultra distances but it seems like that’s the ideal place you’d want to be in.4 Main Things I Learned

1) Nobody is born a “runner”, or anything else for that matter.

What I mean by that is all these titles - “runner”, “powerlifter”, “basketball player”, or “whatever-er” - aren't inherent. People aren’t born as these things. You get these titles as you do specific kinds of work, shape your body in certain ways, and get better at certain things. Maybe doing this work, shaping your body in a certain way, and getting better at certain things happens easier for some people in certain situations which makes it seem like they’re born with it. If both your parents trail run and took you on trail runs for fun growing up, and then one day you end up a decent trail runner it’s going to look like you were born that way. In reality you had to complete the same amount of work as anyone does to become a decent trail runner, you just did it when you were young, and it just looked and felt a little easier because of your environment and enjoyment. You could pick most anyone off the street and put them through the same thing and they’d become decent trail runner. Feel free to replace “trail runner” with any other “-er” title. This isn't the first time I've had this tought. The first time was becoming a “powerlifter”. I lifted weights regularly, had done so for a number of years and was very into it, but I didn’t identify as a “powerlifter” and didn’t see any way I could ever become one. Those guys are bigger, stronger, and better than me. They’re crazy people. Until I made the decision to hire a coach, do the specific work, put on some weight, and get better at squatting, benching, and deadlifting. All of a sudden I did a competition and people started calling me “one of the powerlifters”.Me, doing my best powerlifter impression.

This 50k was the second time experiencing this, and was the way bigger eye opener. When I started I was still grouped in as a powerlifter - I lift, I eat, I hate cardio. Runners are tiny, they grew up in the mountains, they love to run. I weigh 200lbs, I grew up on a wet rock in the Atlantic, and I hated running. Literally until the moment I arrived at the lighthouse in Cape Spear and my Strava ticked 56.4km I wasn’t sure that I could finish. But I did the specific kinds of work that trail runners do, shaped my body to be more like a trail runner’s, and got better at running on trail for a long time. Turns out the same 200lb stocky body that used to be called a “powerlifter” can also become a “50k trail runner”. So think twice before putting yourself in these boxes and accepting limits because they don’t really exist. Genetics play a huge role (especially at the higher levels) but nobody on this earth can avoid having to do the work, adapting their bodies, and learning the skills that are what makes someone earn one of these “-er” titles. You can be any kind of “-er” you want - there aren’t any limits.2) Start slow, and keep things feeling easy for as long as you can.

My first run was 3.5km with pretty much zero elevation gain, and I slowly bumped things up in a way where training was never unmanageably hard. It sure got uncomfortable at times, but I rarely pushed things to a point where I felt like I didn’t have a single kilometre left in me. It made going from 10k long runs all the way up to around 25k feel around the same difficulty. Things didn’t really get funky until the 30k mark. I think this little “pocket” of training where things are challenging, but not overwhelming - where things don’t feel easy, but don’t feel unmanageably hard - is what you should be shooting for in most domains of training. At some level success with training will always boil down to how long you can keep training productively, and this pocket is where the most sustainable training seems to happen.It is so much easier to bump things up little by little than to accidentally bump things up too much, cause some sort of overuse injury or make yourself sick of training, and then try to backpedal to fix it while you’re also still hellbent on progressing forward. For me this meant progressing running volume at a rate my body was 100% equipped to handle. Not backing off when I felt some signs of knee pain, but backing off a little before that. Hitting the ceiling too early makes things exponentially harder, but if you can stay a little bit underneath the ceiling while slowly pushing the ceiling higher, things feel way easier and you’ll be able to get better for way longer before having to rest or backpedal.3) Keep things enjoyable.

Going into this, I was already into hiking, and there was a list of new trails I wanted to explore. So when I first started on my first trail run it didn’t even feel like I was training - it just felt like running around in the woods and exploring. Hiking but faster. I’d nibble on some gummy candy to keep my body fuelled but also because they’re tasty. I’d stop to explore all the little lookout points, to look at squirrels, or take a selfie to put on Strava. The priority for a solid 75% of my training was just running around the woods and having a good time, which made it all feel like a bit of a laugh and not really like hard training (even though it was). Sure I could have swapped the Swedish Berries for gross sugar gels, and never stopped to take in the scenery but the end result wouldn't have been much different. So why not at least try to enjoy it a little? A squirrel pic from one of my trail runs. Plump.

In the past I’ve had the old school mentality of “if I’m not bleeding or crying it’s probably not doing anything for me”, which I’ve since come to realize (several times over) is foolish. If you can get the same work done and make it feel like half the effort, why wouldn’t you? That way you can maintain that level of training for longer, reach a higher “peak” in the long term, and it sucks way less on the way there. That way when it’s “time to bleed” you have one extra gear in reserve that you can tap in to if you need to. While there are definitely times where doing truly gritty and hard training is necessary, I think from here on out I’m going to be a lot more selective with how often and when that is. 4) Prepare for potential problems before they become problems

I think a lot of people (myself included) can probably take a good guess at where 80% of the problems will occur over the course of their training, but just fail to address them for whatever reason. For me it was “overuse” knee issues, and ankle problems. I’ve been aware of both for many years, but that hasn’t stopped me from doing nothing about them and letting them derail productive training in the past. I think everyone who has trained for something for a few years has one or two of these areas that they’re well aware of.I’d fall into the trap of thinking “this achy area used to feel fine, and it feels fine again right now, so it’s not something I need to worry about ever again!”. But once fatigue starts to accumulate and training gets hard, these old nagging injuries always have a way of wiggling up to the surface again, and slowly degrading the quality of training or derailing it totally.

When planning out training, beginning with the assumption that your training WILL get derailed by one of these known issues could be a practical strategy for preventing this whole scenario. For this 50k I consciously started with the assumption that my knees and ankles were 100% going to be a problem at some point, just because I’ve had some issues with them in different contexts in the past. Throwing in some extensive plyos to build my knee's tolerance to impact stresses before they started to hurt, and strengthening my feet and ankles before they had the chance to limit my training were simple things to do that required minimal effort or time. Whether it saved the whole prep or not, these things are low hanging fruit that require minimal effort to address, and have the potential to have a huge impact. Wrapping It Up

To wrap this debrief up I want to give a huge thank you to everyone who shared the fundraiser with friends, donated, or supported in any way. With regards to running, I’ll be taking a little break to focus on other things in my training, but I’m excited to see what the next thing is that gets me fired up to train as much as the idea of training for this 50k did. I hope you were able to find a couple nuggets of wisdom in reading about the whole process and can see how they might apply to things in your own athletic side quests.