Sneaking in Strength: How to Strength Train with No Time

Strength training sessions usually have to be “snuck in” - and that’s fine. If you’re not a strength athlete, strength training plays a supporting role and isn’t your main squeeze. Whether you’re an athlete trying to fit in a couple lifts around practice, a full time working professional first and an athlete second, or a student athlete trying to sneak in a lift between naps and mental breakdowns - everyone who trains consistently will find themselves strapped for time to lift at one point or another.When the time crunch is on and time to lift is scarce, the common approaches for “sneaking a lift in” seem to fall in to 3 main categories:Not doing any lifting, because you can’t do all of it.Condensing your regular strength sessions into less time; being more efficient.Reducing training to the least amount of time you can while still seeing a benefit; a minimalist approach.

Number 1 unfortunately seems to be the most popular approach - it is also the worst option for your progress, and is the reason I wanted to write this article. Don’t pick option 1. The focus should be on options 2 and 3 - both can be great approaches for squeezing in your strength training. If you plan on training for a long period of your life, you’ll probably have to implement both at one point or another. So let’s talk about strategies you can use to either make your training more efficient, or to adopt a minimalist approach for when the time comes.How to Make Your Workouts More Efficient - Fitting Your Existing Training Load Into Less Time.

1. Get rid of general warmups.

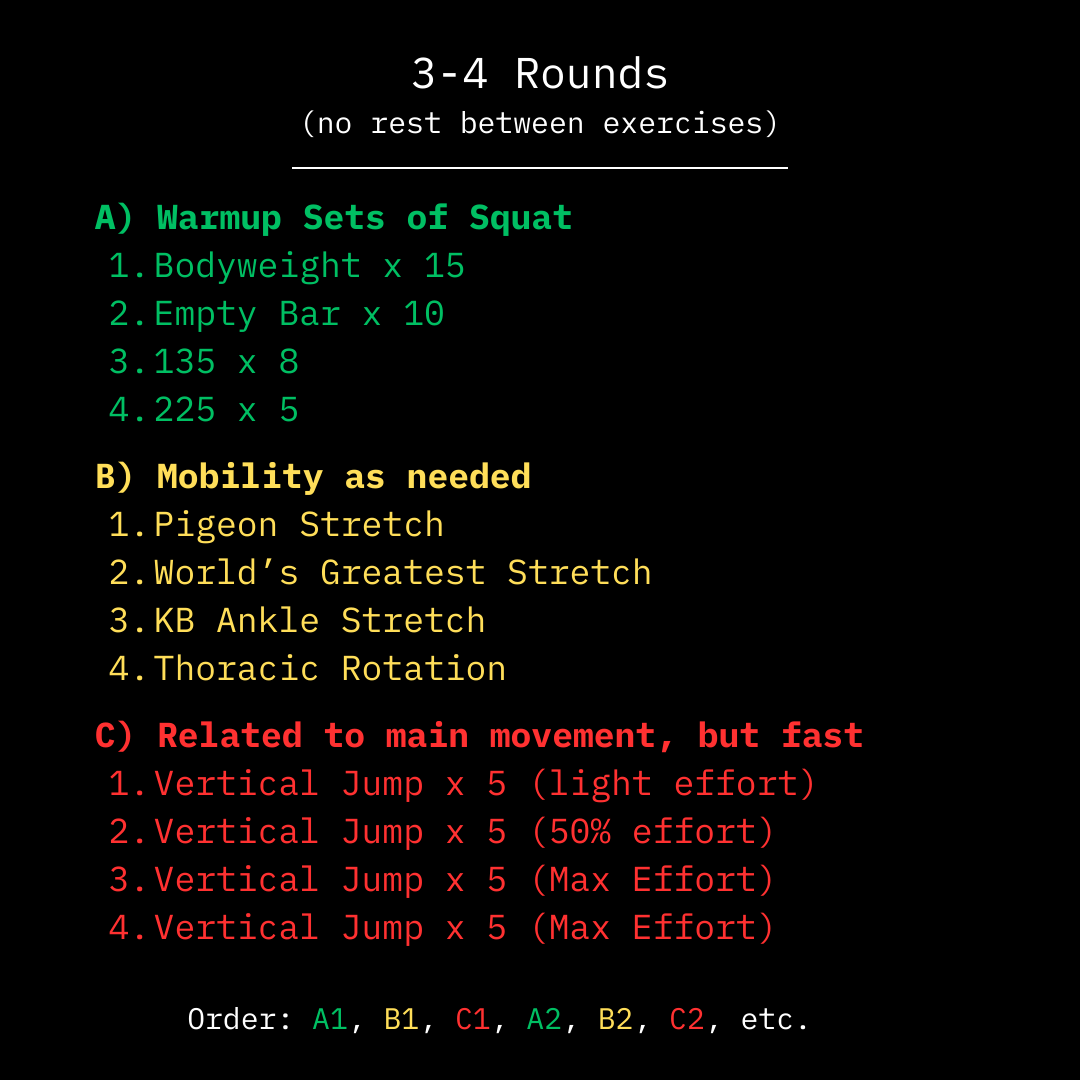

General warmups (ex: time spent on a spin bike prior to doing your specific squat warmup) might not have a positive effect on the following workout (Iversen et al. 2023). Instead of doing a general cardio warmup, then your warm-up or activation exercises, and then moving on to your main lift’s warm-up sets, you can ax the general warmup and condense the activation and warm-up sets in to a quick circuit with minimal rest. This will save you time, and still have you prepared for the workout at hand. Here’s the framework I’ve been using:So a simple squat warm-up might look like this:

2. Stop waiting for equipment.

When planning your program, choose exercises that use equipment your gym has lots of - this means less time waiting. If you’ve been training at your gym for a while you know the equipment that is always taken - if you can get the same benefit from another exercise that uses less popular equipment, always do it. 3. Get rid of idle time by using strategic supersets.

For example:Supersetting main power or strength lifts with unrelated “prehab” work. That way you are recovering from your set of squats and getting non-fatiguing, but necessary work in at the same time.Ex: Heavy squats + shoulder band work, or heavy bench press + calf raises.

Supersetting two exercises that work unrelated muscle groups that use the same equipment. That way you only have to wait for and set up the equipment once, but get to knock off 2 exercises.Ex: Dumbbell Incline Bench Press + Chest Supported DB Row, DB Bicep Curls + DB Lateral Raises, Pec Deck + Reverse Pec Deck.

4. Get rid of even more idle time by using rest-pause and drop sets for hypertrophy work.

A rest-pause set means that you do a normal set to failure, rest about 20 seconds, then immediately perform another set to failure while fatigued. Already being fatigued means it will take less reps (and time) to reach your “failure point” in the next set. Ex: Bicep Curl Rest-Pause Sets

Set 1: 30lbs for 12 reps (to failure)

~20sec rest

Set 2: 30lbs for 8 reps (to failure)

~20sec rest

Set 3: 30lbs for 6 reps (to failure)

In a drop-set, you would perform a normal set, reduce the load 10-25%, and immediately perform another set to failure, normally repeating this process 1-3 times.Ex: Bicep Curl Drop Sets

Set 1: 30lbs for 12 reps (to failure)

No rest

Set 2: 25lbs for 11 reps (to failure)

No rest

Set 3: 20lbs for 9 reps (to failure)

Both methods allow you to “approach failure” many times within a short timespan, making it beneficial when training for muscle size. Both approaches are best used with isolation lifts, not with anything like squats, or bench. Both methods have been shown to be effective for muscle growth (Iversen et al. 2023), but probably aren’t great choices for getting stronger or more powerful. 5. Focus on exercises that have the biggest impact on your goals.

You have limited time to train, so you should be spending it on things that have the biggest impact. This could mean focusing on movements that are precise in training for your main goal.Ex: If your main goal is a stronger squat - devote your time to the squat, even if it means rushing through the unrelated accessories.Ex: If your main goal is getting a higher vertical - devote your time to jumps and close relatives (cleans, weighted jumps, squats). Upper body work, or unrelated accessories can be rushed or skipped when needed.

This could also mean focusing on movements that hit multiple “bases".Ex: You could choose to do a leg extension, back extension, adductor machine, etc., or you could just add in an extra set or two of squats to work all the same muscles at once.

Ex: If you need to stretch your chest and want to train your biceps use an incline bicep curl to do both at once.

If you’re able to use a few of these approaches when designing your workouts, you should be able to shave anywhere from 5-30 minutes off your total training time - which can be the difference between getting it done or not some days. If your time constrictions become so tight that condensing your existing training load with these strategies still leaves your workouts too long to sneak in, a period of minimalist training could be a great idea.How to Use a Minimalist Approach - The Least Amount of Training it Takes to See Results.

The approach most people take is a maximalist one - this is where you shoot to do whatever you need to do to get the most progress as quickly as possible. Minimalist training is the flip side to this - where the goal is to do the least amount of training that it takes to see results. By nature of doing less, you’ll spend less time in the gym.A minimalist approach does come with inherently slower progress, but when you take consistency into account - the minimalist approach will actually yield better progress than the maximalist for some people in the long run. Maintaining a small amount consistently for many years will get you farther than doing a large amount infrequently. That said - the difference between a minimal and maximal approach seems to be much smaller than you’d think. A meta-analysis by Ralston et al. showed that 81% of maximal strength gains can be made with just 1-4 sets per exercise per week. A review and meta-analysis by Schoenfeld et al. (2017) suggests that 1-4 sets per muscle per week can get you 64% of maximum muscle growth gains. So if minimalist training is all you can sneak in, you’re still getting the majority of the gains.Here’s a framework I’ve used to write minimalist sessions that gives you the 1-4 sets at high percentages for strength, and 1-4 sets taken close to failure on other major muscles for muscle building.

I include some power work because to cover the high speed resistance training “base” - which has been shown to be better than slow speed resistance training for developing muscular power (Kawamori 2004), even though minimal recommendations for power aren’t as clear.

From there you can fill in the template with exercises based on your needs, the demands of your sport, and the demands of your life. For example, a session for a basketball player lacking in vertical jump might shape up like this:It doesn’t seem like much, but it is more than enough to make significant improvements in the way your body moves, or to maintain what you have already worked on until you can get back to more maximalist-style training.To sum it all up - if you haven’t had to modify your training to fit within life’s demands you probably haven’t been training for long enough. When the time hits, first try to maintain your current workload by using strategies to reduce the time it takes to complete. If that’s still too much, go minimalist. You can always add more training when life outside the gym eases. When in doubt, whatever helps you continue training consistently for the longest period of time is the right answer.I’m always happy to chat about how these things fit with your individual circumstances - you can book a video consultation here at no cost, where I guarantee you’ll leave with actionable direction towards your goals. References:

Iversen, V. M., Norum, M., Schoenfeld, B. J., & Fimland, M. S. (2021). No time to lift? designing time-efficient training programs for strength and hypertrophy: A narrative review. Sports Medicine, 51(10), 2079–2095. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01490-1

Kawamori, N., & Haff, G. G. (2004). The optimal training load for the development of muscular power. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 18(3), 675–684. doi:10.1519/00124278-200408000-00051

Ralston, G. W., Kilgore, L., Wyatt, F. B., & Baker, J. S. (2017). The effect of weekly set volume on Strength Gain: A meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 47(12), 2585–2601. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0762-7

Schoenfeld, B. J., Ogborn, D., & Krieger, J. W. (2016). Dose-response relationship between weekly resistance training volume and increases in Muscle Mass: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences, 35(11), 1073–1082. doi:10.1080/02640414.2016.1210197