How to Progress When Adding More Weight Doesn’t Work

The good ol’ days don’t last forever - those days where you can hit a 10lb PR each new session are a beautiful time to be alive, but it’s usually short lived. Eventually you need to think about different ways to keep the gains coming that don’t just involve adding more weight.The reason adding 10lbs each week works is because it makes the movement harder, which provides a new challenge to your body and gives it a reason to adapt. As your body gets better adapted to the training you put it through, that training needs to continue to get harder in order to continue giving your body enough of a reason to adapt. You might know this concept as “progressive overload”. In the same way adding weight makes a movement harder by making it heavier, there are other progression methods that make different aspects of movements harder by changing a different exercise variable. Each of these progression methods also provide the body with a reason to adapt, and each have their own specific time and place.1. Progress the Sets, Reps, or Frequency.

It’s simple, but the list would be incomplete without it. And if the simple stuff gets you results, then guess what you should be doing? Adding more sets, reps, or frequency are all just ways of increasing volume. Handling more volume (even with the same weight) can be an effective way to grow muscle, get stronger, or increase work capacity.In your program, this can be as simple as:Performing 10 reps with a certain weight one week, and shooting for 12 reps with that weight the next.

Bumping up how many sets you perform on an exercise every 2-8 weeks.Increasing how many times a week you work a certain lift.

2. Progress the Speed with Tempos and Pauses.

You can also progress a movement by changing the speed of the exercise by adding tempos or pauses.Adding a pause during each rep can be especially useful if there is a specific part of the movement where you tend to fail your reps. Pausing at that point can help you build strength there, and also give you time to correct faulty positioning. For example, athletes who have trouble with their deadlift right as it lifts off the floor often benefit from a 2-3 second pause when the bar is at mid shin, right when the bar lifts off the floor. It helps them build strength in this low position, but arguably more importantly it gives them an extra second to think about if they wedged into their deadlift correctly, and if their position should be corrected on the next rep. Tempos can similarly help you gain control at different parts of a movement, also by making a portion of the movement harder, and by giving you more time to think. For example, if an athlete struggles with controlling their descent on the squat, adding a 3 second eccentric tempo forces them to spend more time controlling the descent, giving them time to make corrections to their position and building the necessary strength to do so. Depending on your goal, speed can also be progressed in the opposite direction - by making a movement faster, such as when training to develop muscular power. If you can move a given weight faster week to week, you’d be providing an overloading stimulus as well.Some other examples include:Adding a 2-count pause on the bottom of a bench press rep to help with control off the chestAdding a 3 second eccentric tempo to a chin up to build strength for your first assistance-free repPausing a depth jump to give you time to think about your landing position before jumping again

3. Progress the Stability / Base of Support.

Keep your bosu ball tucked away in the closet, that’s not what I mean. Think of this as manipulating how much stability you are given from the setup of an exercise vs. how much stability you have to work to create on your own. There are many ways to do this, but is most commonly done by altering the stance you use for a given exercise.A good example is comparing a normal bilateral squat to a split squat. In a normal squat, your hips have relatively low freedom to move. Your right leg pushes into your left and vice versa, and both sit directly beneath your hips - creating lots of stability in your lower body just by the setup of the exercise. If you change to a split stance, one leg no longer has the other to “brace into” which gives the hip more freedom to move on one side, and one hip no longer has a leg directly underneath for support. More freedom to move means you have to create more stability on your own in order to produce the force necessary to complete a split squat. It is worth knowing that instability and force output have an inverse relationship - the more unstable the exercise, the less force you’ll be able to put out. This is part of the reason you can split squat more than you can pistol squat, and why you should keep the bosu ball hidden in the closet if you’re training for max strength. Keep this in mind when training for goals that depend on a high force output like strength and power.

Some other examples include:Progressing from a chest supported row to a bent over row - (having a pad to support your torso vs having to stabilize it yourself).

Progressing from a lat pulldown to a pull up - (being stabilized by a seat vs having to stabilize the swing of your own body).Progressing from a split squat to a backward stepping lunge - (the added time spent on one leg while stepping back adds instability).

4. Progress the Range of Motion.

Given the same weight, a longer range of motion will make an exercise harder, and shorter range of motion will make it easier. You can either restrict, or extend range of motion to progress movements for different goals. Restricting the range of motion allows you to handle more weight in a shortened range, which helps you build additional strength in that portion of the movement. For example, an athlete who has trouble locking out a bench press might benefit from a board press - which would eliminate the bottom of the range of motion and emphasize the lockout, overloading the weakest portion of the lift. Extending the range of motion will make the exercise harder by putting the joint through new ranges of motion, and having to control weight for more time per rep. For example, an athlete who has mastered the normal pushup might benefit from a deficit push up which makes the time controlling their bodyweight longer per rep, and puts the shoulder through a greater range of motion. Some other examples include:Progressing a 6 inch step up to a 10 inch step up.Using Block deadlifts to overload the top half of a deadlift.Progressing normal Romanian Deadlifts to Deficit Romanian Deadlifts - to allow the bar to travel further without hitting the floor.

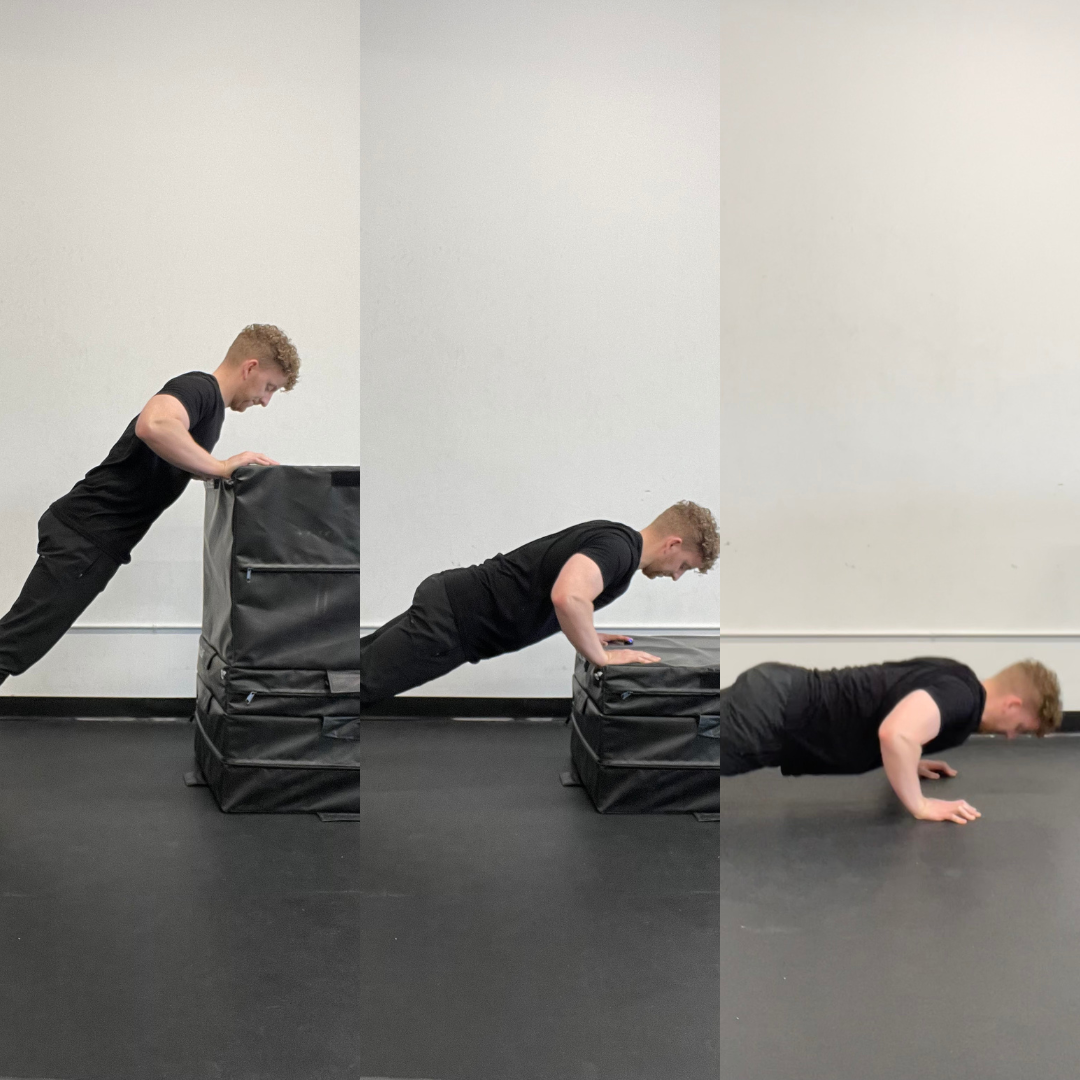

5. Progress the Angle.

Progressing the angle of a movement could mean changing the angle of equipment like cables or bands, or could mean changing the way your body and weights are situated in relation to the pull of gravity. This can be especially useful when programming bodyweight exercises, but can be used in other scenarios as well.For example, very new trainees will often start with a high box pushup. They progress by moving their hands to a chest-high box, then hip-high, then knee-high until their hands are on the floor cranking out push ups. Lowering the box makes the exercise harder by making more of their pushing force in line with gravity. You can continue with this same principle by elevating the feet on higher and higher boxes next to continue to overload via a simple change in angle.

Some other examples include:Progressing from a TRX row to a Chin up.Progressing from a cable curl towards the cable anchor point to facing away from the anchor point.Progressing a side plank to a feet elevated side plank.

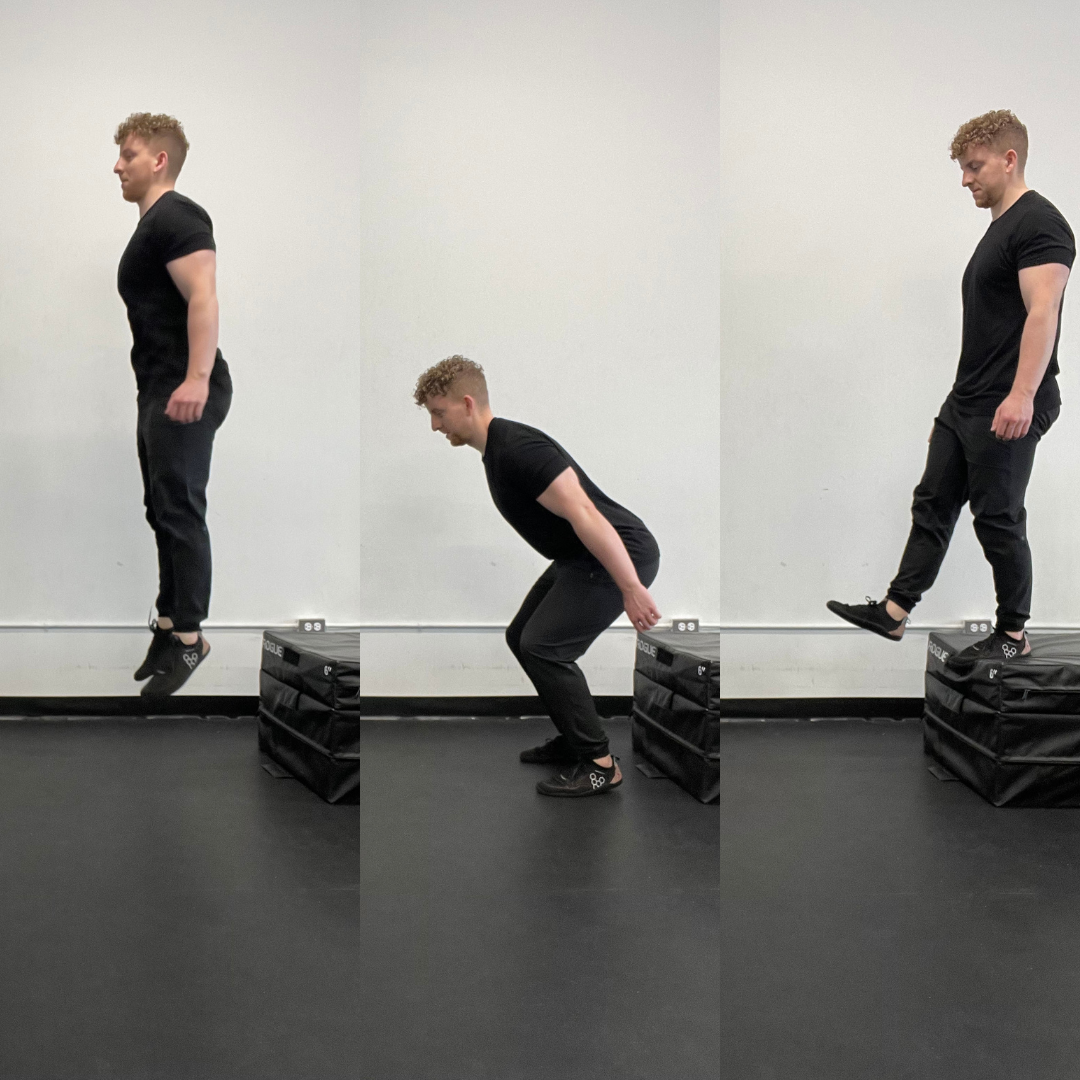

6. Progress the Movement Complexity.

Adding a hurdle to jump over is a simple way of increasing complexity on jumps.

This one is a little more broad - increasing movement complexity can look like a lot of different things, but the general idea is that you are adding more elements to the movement being performed. When increasing movement complexity it is usually to develop movement skills.

This is a great way of progressively teaching someone a new and complex movement - for example teaching someone to hang clean by starting with an RDL, then RDL-to-shrug, then shrug pull, high pull, and eventually hang clean.

I most often use complexity as the main progression when introducing jump training - starting by practicing jump landings with something like a box-step-off, progressing to a non-countermovement jump, countermovement jump, and eventually stringing multiple jumps in succession, or adding a rotational component. Some other examples include:Progressing from a split squat to a lunge - the added unpredictability of stepping adds complexity.Adding things like rotation or pre-hops to existing plyometrics.Adding implements (like hurdles) to clear on jumps.

7. Progress the Density.

Density is just the ratio of work to rest - so you can progress by either increasing the amount of work, or decreasing the amount you rest. This works well when developing capacity related traits - that could be conditioning, aerobic fitness, or work capacity with weights. One example of this is progressively decreasing rest times on a movement. Maybe you did 3 sets of 15 on a barbell row with 185lbs and 1:00 rest in between sets. The next session you could try the same 3 sets of 15 with 185lbs, but decrease your rest to :45 seconds, then :30 seconds after that. You’ll be entering later sets with more and more fatigue, making them more difficult to complete, and providing progressive overload. Between progressing volume, speed, stability, range of motion, angle, movement complexity and density you have a whole bag of tricks to progressively overload and keep your body adapting. As you combine these methods and try them in different scenarios, think about the ways movements connect and build off one another. While the days of hitting PR’s every week might be behind you, having a variety of ways to develop different all the different aspects of strength will keep you hitting PR’s for many years to come - and that’s where the really fun progress happens anyway. If you’re still stuck on how to keep getting stronger, you can book a 30 min chat with me here (at no charge) to talk about how we can get you progressing again.